Permanent Exhibitions

Path into the depths

Exhibition in the vault of the ring kiln

The example of the ‘Hercules’ shaft from 1839 brings an important chapter in mining history back to life: the transition from tunnel mining to underground mining marks the transition from a rural area to an industrial region.

On their way down into the depths, the miners had to overcome numerous obstacles and solve problems. They needed light and air to be able to do their work in the pit. And it wasn't just coal that was extracted from the shaft; water also had to be continuously pumped out of the pit.

Visitors enter the unknown underground world through a ‘dark zone’. Models here illustrate, for example, how the branched system of fresh air supply worked and what the ideal layout of an underground colliery looked like. A separate area is dedicated to the much-praised ‘light in the night’. These and other topics are dealt with in an unusual exhibition venue: after the colliery was closed down, the shaft was vaulted with a brick ring kiln.

Dünkelberg Brickworks

Exhibition in the ring kiln

In 1892, the last year of the colliery's operation, building contractor Wilhelm Dünkelberg acquired the site that is now the museum. Between 1897 and 1899, the double ring kiln complex, which still dominates the site today and could fire up to eleven million bricks annually, was built on the site of the colliery buildings around the Hercules shaft.

The raw material for the bricks was slate clay, which is found in the Ruhr Valley below the coal seams. The exhibition in the eastern ring kiln follows the path of the raw material: from the extraction of the material in the quarry to its processing, firing in the ring kiln and loading of the bricks, visitors learn about the everyday life of brickmakers up to the 1960s.

Inside the ring kiln, bricks and blanks are stacked, dust and ash cover the floor of the workplace. Illuminated pictures and quotations from the working world of the brickmakers support the spatial effect of the monument. Bricks and sandstone used to be loaded at the Ruhr Valley Railway ramp. In a railway carriage, the museum shows how urgently the stones were needed during the rapid industrial development of the Ruhr area around 1900.

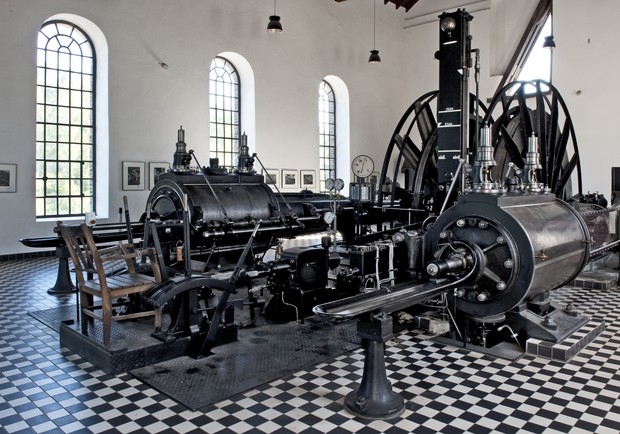

Steam-powered transport machine

The steam-powered transport machine from 1887 is one of the oldest examples of its kind in the Ruhr mining industry. It was last used at the Prosper Haniel colliery in Bottrop before coming to the Industrial Museum in Witten. The workshops have restored the machine to working order with the help of an electric motor. Demonstrations take place regularly. You can find the dates in the events section.

Coal shipping on the Ruhr

Ruhr boat and water playground

An important location factor for the Nachtigall colliery was shipping on the Ruhr. After it was made navigable in 1780, the river developed into the most important transport route for hard coal. The centrepiece of the exhibition is the reconstructed Ruhr barge ‘Ludwig Henz’. The ship, which is over 35 metres long and five metres wide, was built between 1999 and 2002 as part of a training programme for unemployed young people. Its name commemorates a hydraulic engineer from Hattingen who was heavily involved in the development of transport in the Ruhr Valley around 1840.

The ship focuses on coal shipping between Witten and Ruhrort: what did the Ruhr look like back then? What difficulties did the skippers have to contend with? The shipbuilding site focuses on historical shipbuilding on the Ruhr, but also on the replica for the museum.

The coal depot, a replica of a typical storage area on the river, focuses on the coal trade. The history of the river plays a major role. The question ‘What happened when the river was made navigable?’ can be explored not only using the model: a water playground invites children to experiment.

With the arrival of the first railways in the Ruhr Valley, coal shipping faced competition. When the Nachtigall colliery connected to the rail network in 1849, the river lost its importance as a transport route. Just under 40 years later, shipping was discontinued. The reconstruction of two carriages from the Muttentalbahn railway, built in 1829, shows how modest the beginnings of the railways were.

Colliery Bucketful

Small coal mines in the Ruhr region

The exhibition ‘Zeche Eimerweise’ (Colliery Bucketful) commemorates the small coal mines of the Ruhr region. Created out of necessity in the post-war years, more than 1,000 small and micro coal mines were in operation between Dortmund and Essen from 1945 to 1976, many of them in the Witten area. The functional replicas on the museum grounds, together with photos and documents, illustrate how such small businesses operated.

Miners and entrepreneurs have their say in the exhibition itself, reporting on the simple technology, administration and hard work involved in small coal mines. The easily comprehensible installations allow even those unfamiliar with mining to understand how a mine worked.