A place that tells many stories

By Ingrid Telsemeyer

Tunnel mine, underground mine, brickworks, sandstone quarry, machine factory, wreath-making workshop, scrap yard, museum – the Nachtigall colliery site has been used for a wide variety of purposes over the past 300 years. Much of this was based on the geological conditions. The sequence of layers of shale clay, coal and sandstone characteristic of the Carboniferous period provided the raw materials.

The Beginnings

According to records, the first application to extract coal from a coal seam in the ‘Hettberger Holtz’ was submitted in 1714. Initially, several farmers from the region were shareholders in this field. In 1743, the landowner Baron Friedrich Christian Theodor von Elverfeldt bought all the shares from them for 140 Reichstaler. The male descendants of the noble family von Elverfeldt then spent more than a century as entrepreneurs in the coal business themselves.

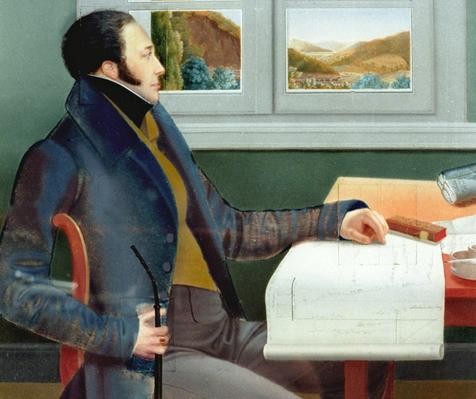

Levin von Elverfeldt (1762–1830) was one of the pioneers of mining in the Ruhr region. When he took over his father's business in 1787, he became heavily involved in mining and the coal trade, accumulating mining properties. By the end of the century, he owned shares in 39 mines along the Ruhr. However, his hopes for business success were not fulfilled. Ludwig von Elverfeldt (1793–1873) took over a heavily indebted estate in 1825. He was responsible for the transition to underground mining, the construction of a horse-drawn railway for transporting coal and the expansion of the colliery.

Tunnel construction

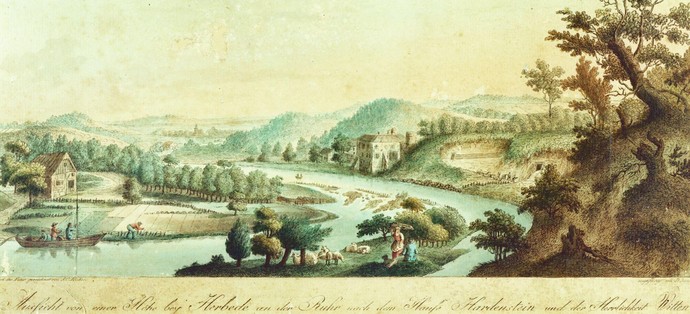

View from a height near Herbede on the Ruhr towards Hardenstein Castle and the Witten estate, around 1780. Two mouth holes can be seen on the slope on the right.

Numerous other collieries around Hettberg mined coal alongside and above each other. Initially, the predominant mining technique was tunnel construction. Horizontal tunnels were driven into a mountain and the coal was extracted by hand.

To reach deeper seams, ‘underground structures’ were built. From there, coal and water were transported to the surface in buckets and boxes through sloping shafts. Access to these tunnel mines was via so-called ‘mouth holes’. Some of these can still be seen today in Muttental.

The mining operations of this early phase differed greatly from modern mining in terms of their organisational structure. In the 1750s and 60s, for example, a maximum of eight miners worked in the Nachtigall mine, who – as was customary at the time – were only employed on a daily or weekly basis, depending on the order situation. Around 1800, ten miners worked in various roles at the Nachtigall tunnel mine: coal cutters and rock cutters for tunnel construction and coal extraction, as well as cart drivers who transported the coal from the mining site to the tunnel mouth using pushcarts. In 1806, the old carts were replaced by rail-based wagon transport.

Mining under Prussian administration

Prussia attempted to bring privately operated mining in the Ruhr under state control, boost coal sales and secure the royal tithe – the prescribed taxes – with new laws and administrative structures, including the establishment of the Märkisches Bergamt (Märkisch Mining Authority) in Bochum in 1738.

After conducting inspections, the mining supervisors and experts appointed by the authorities agreed in their negative assessments of mining in the Mark Brandenburg. They attested to disorder in the ‘mining economy’ and overexploitation. After an inspection tour of 28 Ruhr mines in 1782 on behalf of the Prussian King Frederick II, Chief Mining Councillor Friedrich Wilhelm Graf von Reden criticised the poor state of mining in the County of Mark. He lamented the lack of control by the mining authorities and inadequate accounting, summarising: ‘Everyone does what they want!’

With the introduction of the Revised Mining Regulations of 1766, state administration of the coal mines in the Ruhr region was established. However, the so-called principle of direction could only be implemented gradually.

Into the depths

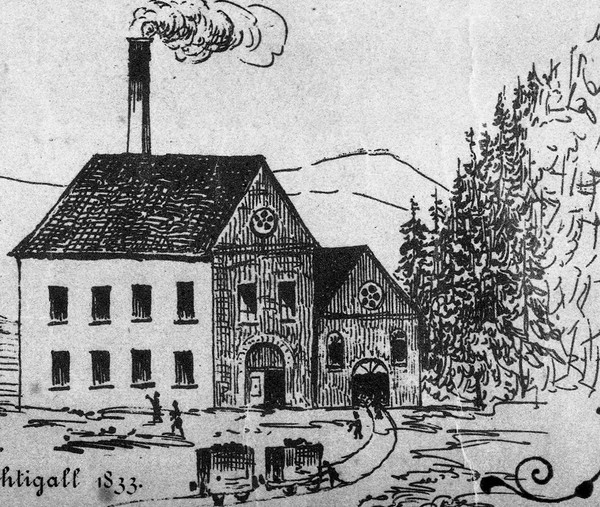

In 1832, work began on sinking the first deep mine shaft at the Nachtigall colliery in order to reach the deeper seams. This had been eagerly awaited, but was nevertheless an experiment with an uncertain outcome, particularly due to difficulties caused by the highly water-bearing rock. The heavy inflows could no longer be managed with hand pumps. This was only achieved with the help of steam engines from the Friedrich Harkort engineering works in Wetter – the innovative technology of early industrialisation.

The 1835 mine operating report reads as follows: ‘Finally, the long-held wish of many has been fulfilled this month. Despite many complaints and obstacles, thanks to providence, the new Neptun machine shaft has been sunk to its destination, the Nachtigall seam, without any serious injuries to the workers.’

In order to cover the investment costs for buildings and machinery, some of the surrounding tunnel mines had previously joined together to form the Vereinigte Nachtigall contractual association. The Eleonore & Nachtigall, Theresia, Wiederlage, Aufgottgewagt, Nordflügel, Braunschweig Nordflügel and Turteltaube Nordflügel mines cooperated, but initially remained independent operations. In March 1835, mining began at the Neptun shaft. New jobs were created for the steam-powered mining and water drainage machines, and by 1836, two guards and two miners were employed there.

United Mining Company Nachtigall

In 1851, Ludwig von Elverfeldt sold his Steinhausen estate and his shares in the coal mines to a group of wealthy Dutch investors who saw mining in the Ruhr region as a promising investment opportunity abroad. They took over a coal mine that was equipped with state-of-the-art technology and had excellent coal reserves.

The investors drove forward further expansion by investing in technical equipment, transport links to the colliery and the new consolidation of the Vereinigte Nachtigall, Vereinigte Nachtigall & Aufgottgewagt, Wiederlage and Theresia collieries into the Vereinigte Nachtigall Tiefbau colliery. In the 1850s and 1860s, this mine employed between 300 and 500 miners. At that time, it was one of the largest mines in the region in terms of number of employees and coal production.

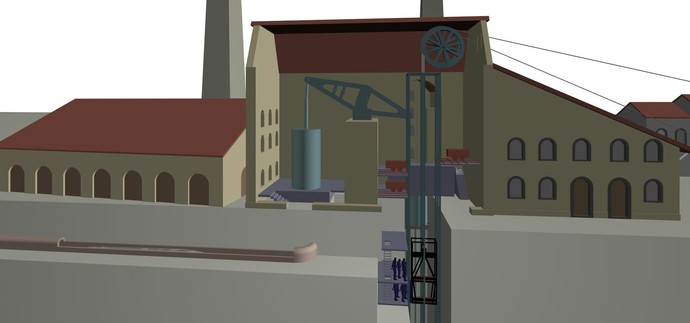

The mine now had three shafts: the Neptun shaft, the Catharina shaft of the former Theresia colliery and the Hercules shaft. The latter became the main extraction shaft of the colliery as a result of further sinking.

In the following years, the colliery expanded its surface facilities and built, among other things, a boiler house, the machine house (which still stands today) and the workshop buildings. The colliery always used the most modern methods available: in 1855, it introduced underground haulage using horses.

In 1857, the most powerful steam engine in the Ruhr mining industry at the time (500 hp) went into operation at Nachtigall. In 1876, modern rope transport was introduced: from then on, miners descended into the shaft in cages suspended from ropes. In 1876, the Hercules shaft reached its maximum depth of 450 metres. Coal production peaked at 100,000 tonnes in 1878. The Nachtigall Tiefbau colliery had reached a state of expansion that did not grow significantly until it was closed in 1892.

The mine struggled with heavy water inflows until it closed. The 1871 annual report of the Nachtigall Tiefbau colliery addressed the vexing issue of water on numerous occasions, which repeatedly caused the colliery to suffer production losses. Operational disruptions became more frequent. By 1882, only 295 miners were still working at the Nachtigall mine. Coal production declined.

The merger with the Helene Tiefbau colliery on the other side of the Ruhr in Heven seemed like a lifeline. Plans were made to mine new seams under the Ruhr Valley, and it was hoped that this would make it easier to finance the necessary investments. However, the colliery overextended itself with the new investments and was forced to file for bankruptcy in 1887. Finally, in 1890, the Dortmund Mining Company purchased the mine. They were interested in the rich mining fields of Helene. Nachtigall, on the other hand, was to be abandoned due to a lack of profitability. The Dortmund Mining Company decided to dissolve the Helene-Nachtigall union.

Discontinuation of coal mining

On 23 February 1892, the so-called ‘robbing’ began at Nachtigall: the sale of machinery and other mining equipment. On 14 October 1891, the Wittener Zeitung newspaper wrote about the approaching end of the Nachtigall colliery:

"Unfortunately, it won't be long before our old Nachtigall colliery, which provides bread and livelihoods for so many residents of our town (...), will work its last shift and be shut down. The main reason for the shutdown is the water calamity (...). In 3-4 months, all the machinery will probably be dismantled, leaving the colliery under water and at a standstill. We are pleased to announce that all workers and officials who were laid off on 1 October have found other work and positions."

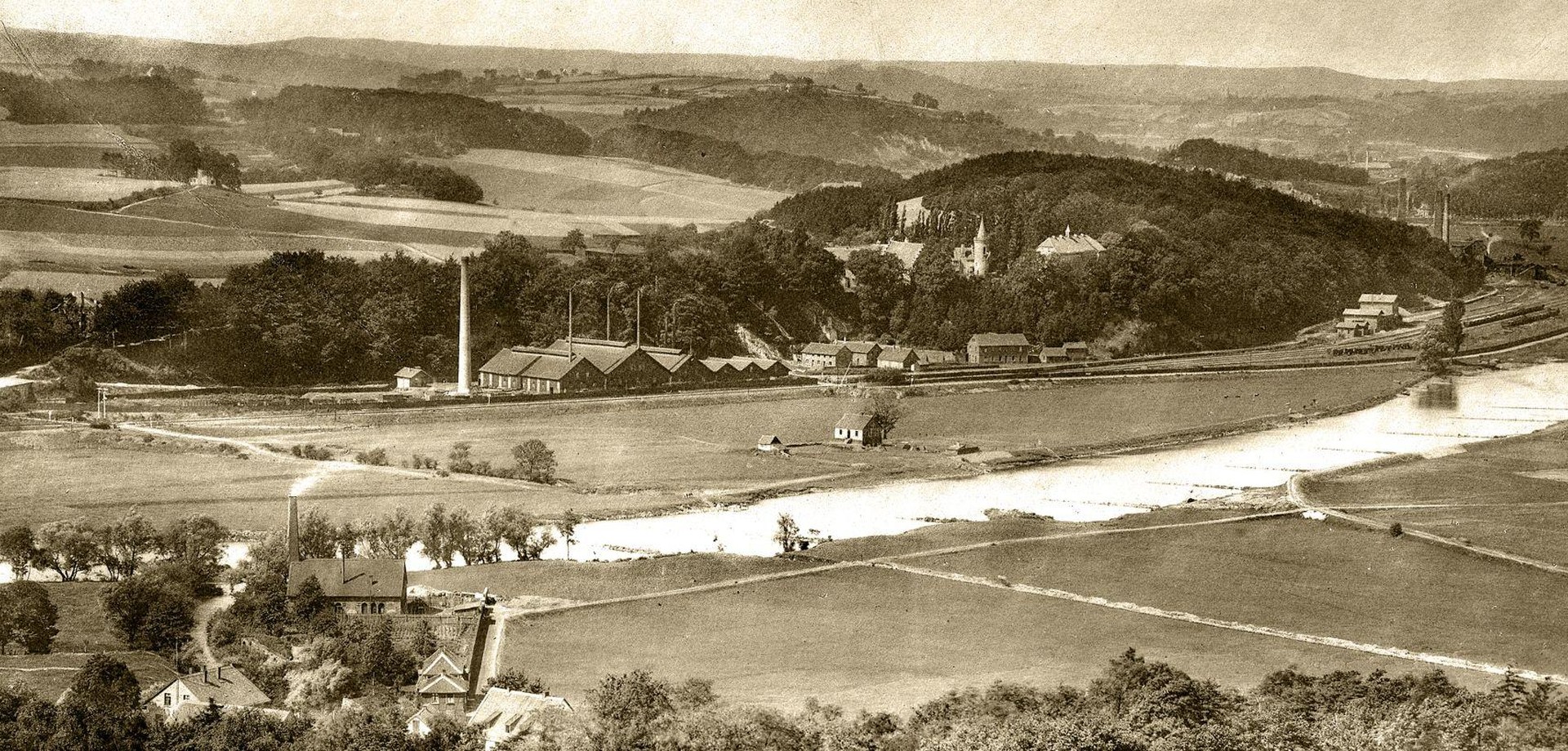

Within a short period of time, the three neighbouring underground mines in the Hardenstein district – Louisenglück, Nachtigall and, most recently in 1906, Ver. Bommerbänker Tiefbau – ceased operations. They were unable to compete with the new, larger mines in the Emscher and Hellweg zones. These had better storage conditions, coking coal suitable for iron smelting and larger coal deposits.

Steam brickworks and sandstone quarries W. Dünkelberg

The wealthy civil engineering contractor Wilhelm Dünkelberg purchased the colliery site in 1892. In the following years, he built a steam-powered brickworks on the site, which began production in 1897, as well as a factory for the manufacture of brickmaking machinery. He extracted sandstone and slate from his quarries.

Most of the colliery buildings were demolished. The machine house, workshop buildings and a boiler house chimney were preserved and repurposed. Dünkelberg had two ring kilns built on the site of the Hercules shaft. The entrepreneur obtained the raw material for brick production, slate clay, from the neighbouring quarry, which belonged to his premises. He had a tunnel, now known as the Nachtigall-Stollen, dug through the Hettberg specifically for this purpose.

The brickworks produced up to eleven million bricks annually for the construction of industrial facilities and houses. Coal mining also continued: to supply his businesses with coal during the coal shortages after the world wars, Wilhelm Dünkelberg used the remaining coal reserves, including those at his small Gottlob colliery.

From scrap yard to museum

In 1963, the brickworks ceased operations, followed later by the sandstone quarry. Small businesses such as a wreath-making workshop and, most recently, a car recycling company used the buildings and grounds. The workshop building served as a residential house. Discarded cars, tyres and oil drums dominated the Nachtigall site. Walkers were soon confronted with a bleak picture of decay.

Committed citizens, monument conservationists and the city of Witten finally recognised the historical significance of the facilities. In 1979, the Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe (Westphalia-Lippe Regional Association) passed a resolution to establish a decentralised Westphalian Industrial Museum, with the Nachtigall colliery as one of the museum's three mining sites.

What was taken over was a historic site with buildings in ruins. What remained were damaged, partially burnt-out and repeatedly repurposed buildings from the mine and brickworks. There was no longer any machinery – instead, there were highly interesting ‘contaminated sites’. Systematic excavations and site work brought many finds to light, layer by layer: scrap metal from the recent past, bricks from the ring kilns of the brickworks, carbon fossils and a historic stone sleeper from the Muttentalbahn railway.

After years of intensive searching for and securing evidence, excavating the Hercules shaft and its surroundings, restoring the buildings, searching for suitable exhibits and developing the museum concept, the Regional Association celebrated the opening of what was then the Westphalian Industrial Museum – now the LWL Museum Zeche Nachtigall – in 2003.

The themes of the permanent exhibition focus on the geology and industrial uses of the site over the past 300 years. The museum's strategically favourable location in the midst of important geotopes led to the National GeoPark Ruhrgebiet establishing its first information centre here in 2014.